Studio Notes 05: Old Yellow Book

designing a 2026 lunisolar almanac

Hi, it’s Lisa Cheng Smith, founder of Yun Hai. I write Taiwan Stories, a free newsletter about Taiwanese food and culture. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, sign up here.

This is Studio Notes, a paid series within that newsletter. It’s an informal exploration of the things on my desk—cultural references, first-hand research, and archival material—all in relation to how we tell stories, create spaces, and design products at Yun Hai.

Your paid subscription supports the free newsletter and our cooking show, Cooking With Steam. If you’re a paying subscriber, thank you so much! If you'd like to read behind the paywall but aren't able to subscribe, I also trade words for words—just reply to this email.

If you happen to be in New York City, don’t miss Taiwanese Waves, a free concert at Central Park featuring up and coming Taiwanese bands and performers, happening this Sunday, August 3rd.

Currently taped up on my studio wall:

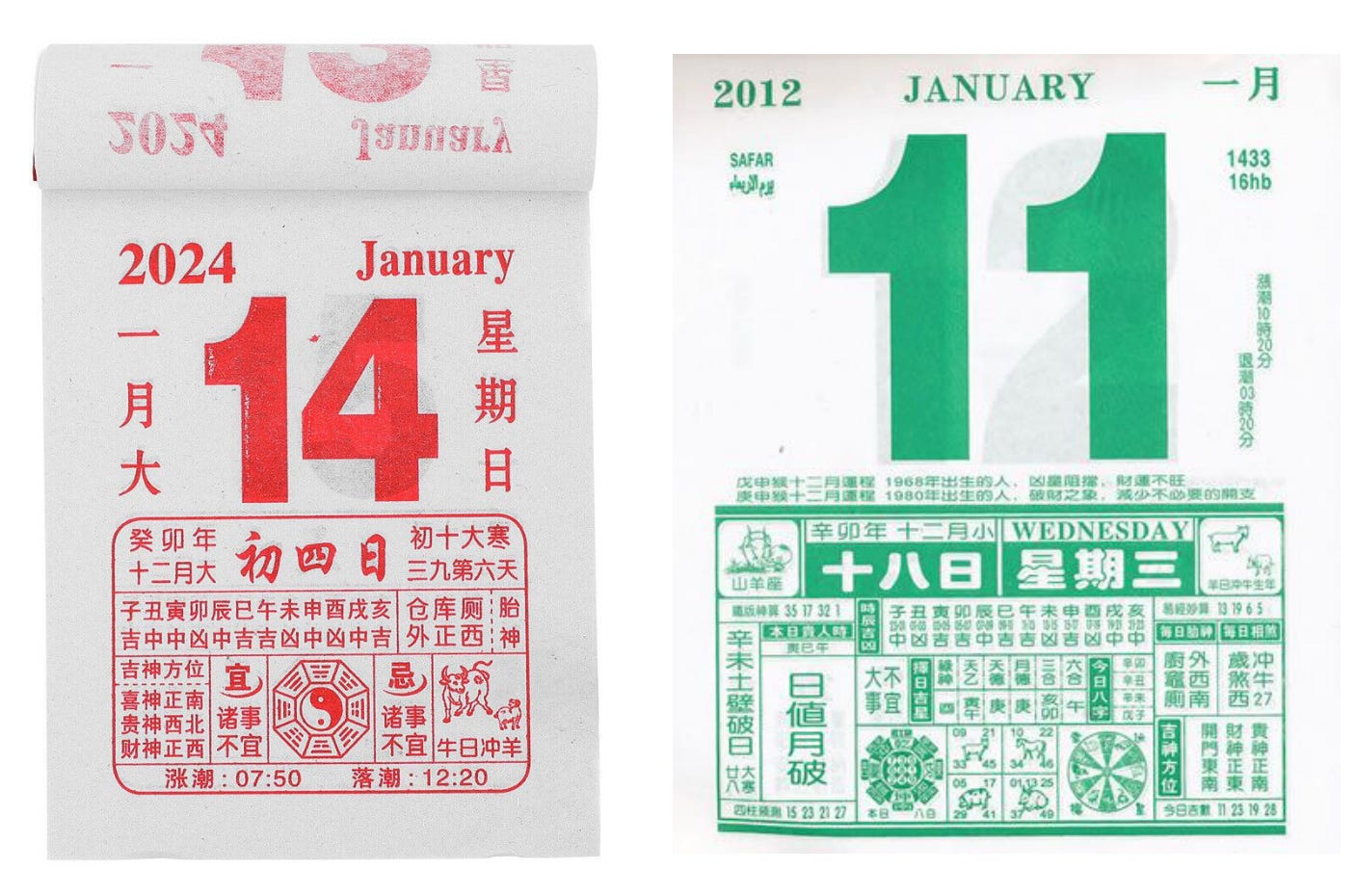

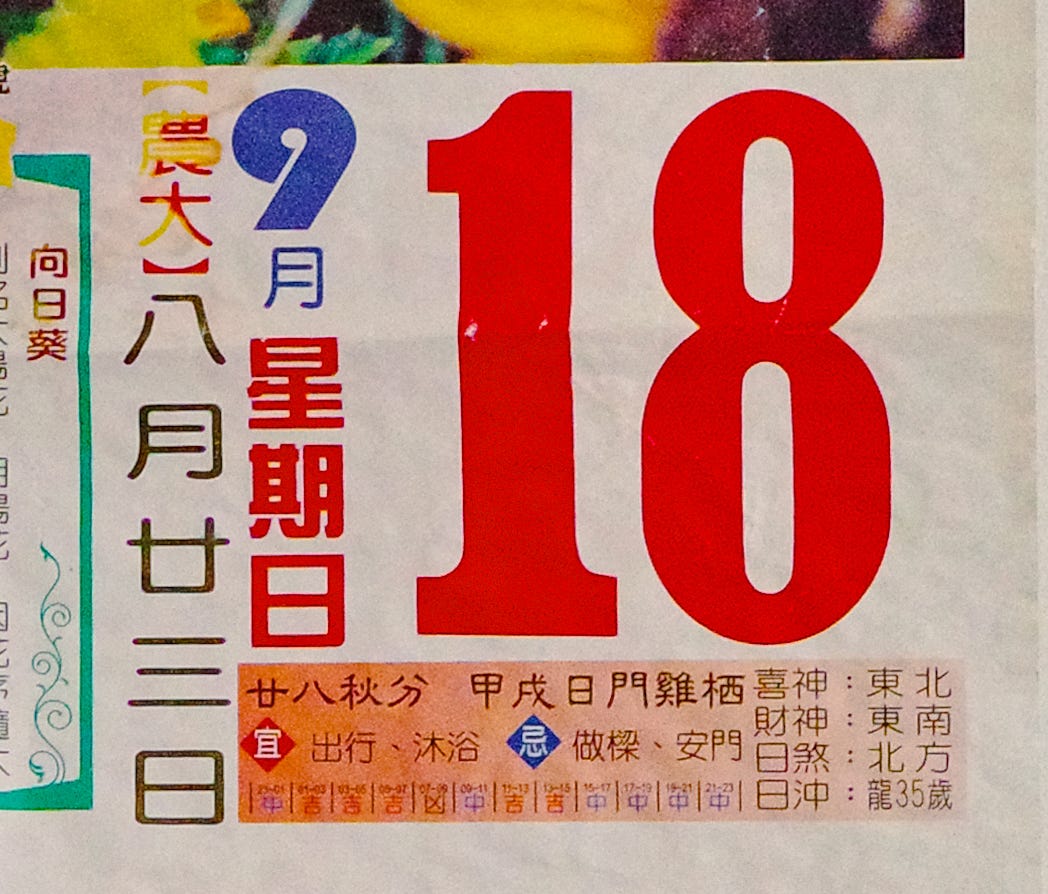

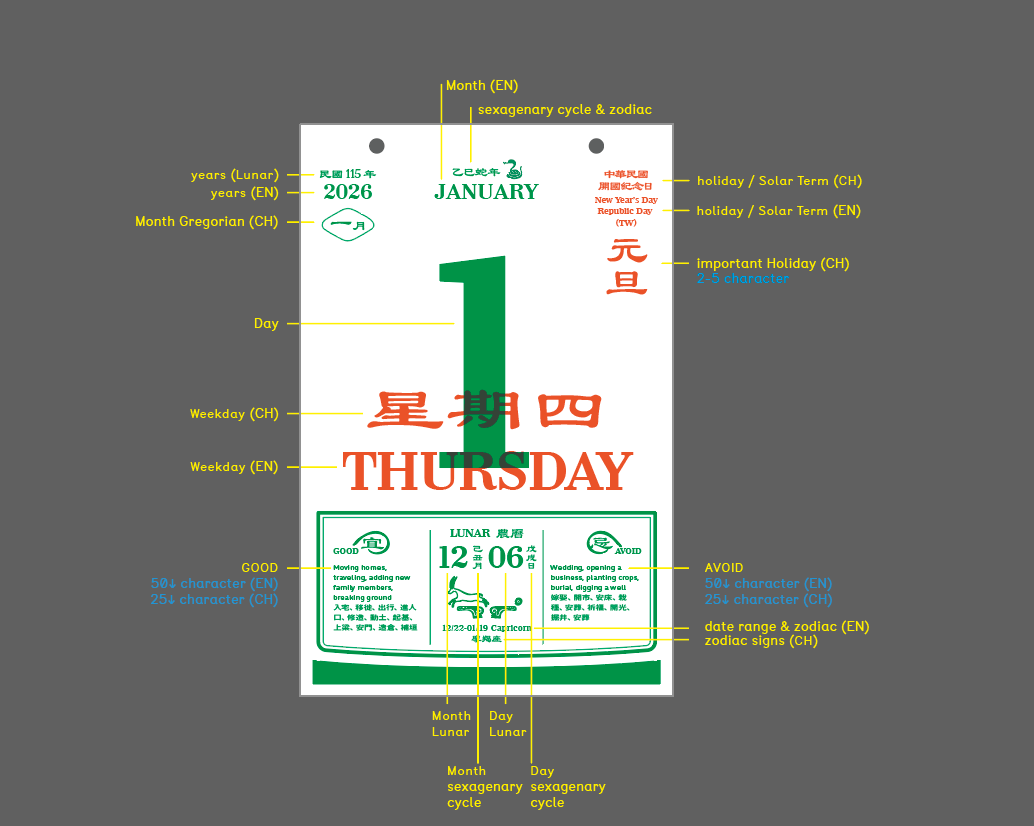

This is a page from a Taiwanese lunisolar almanac. I received it as wrapping paper in a gift from a friend. Though it came to me only recently, the page shows the weekend of September 17th and 18th. The year is there by the little Tiger mascot in the middle: 2022 or 111 年, in the Taiwanese Minguo system.

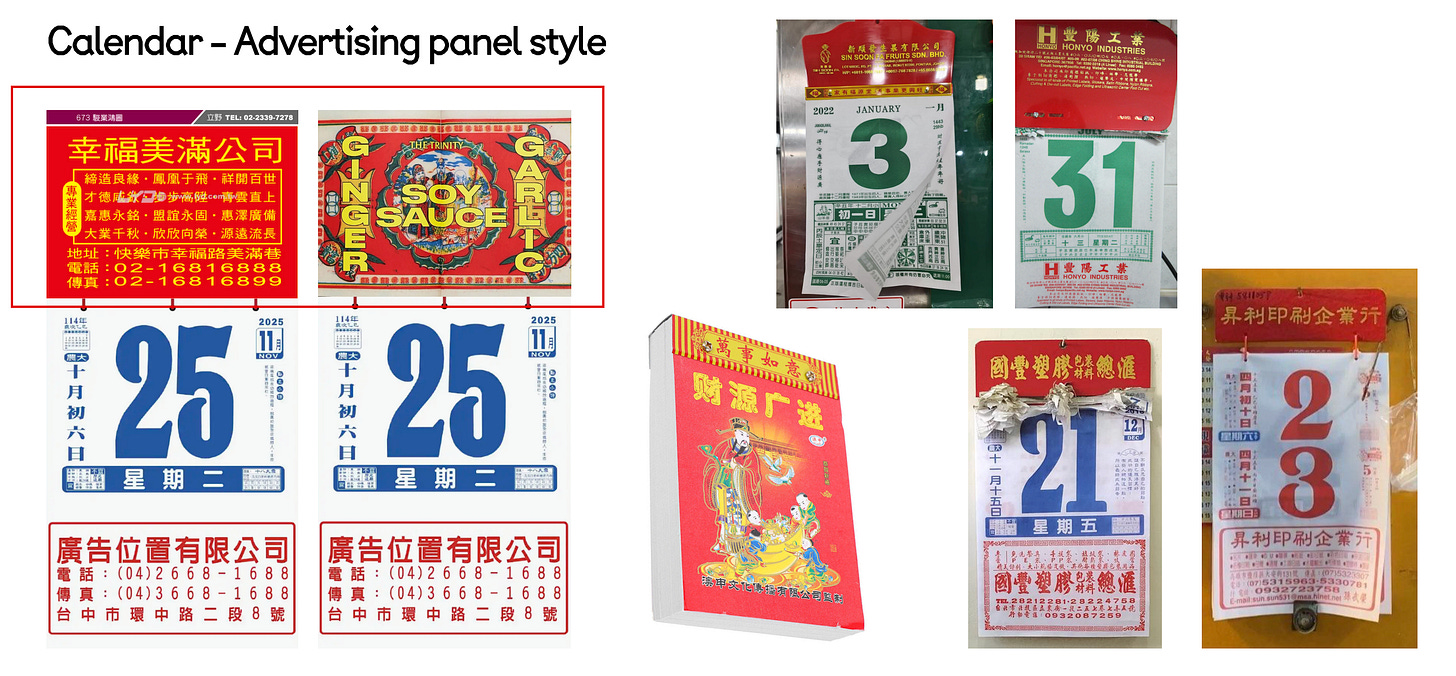

I love everything about it. The sunflower clip art, occupying most of the real estate and reminding me of non sequitur karaoke videos. The densely packed nature of the information, like a newspaper. The mish-mash of typography, calling attention to different sections while solving practical problems. The unembarrassed use of color, border, gradient, and shape. The verbose advert at the bottom, a matter-of-fact persuasion for a flour milling company.

The lunisolar almanac in the Chinese tradition is known by many names, but often as 黃曆 huáng lì, or “yellow calendar.” It’s named this because the almanac used to be the responsibility of the emperor and was identified by imperial yellow. It’s been at the top the bestseller list for over 2000 years (har har) and present in my life since childhood: hanging up on our wall, when we managed to get one; tattered and torn in our favorite shaved ice shops and Taiwanese restaurants; or fragmented into loose leaves to be reused as wrapping or scratch paper. When we receive things from vendors at Yun Hai, we still find almanac pages used to protect fragile items. I save every single one; each a monument to a day.

Beautiful and common, complicated yet plain, these pages were always indecipherable to me. There’s the date, but what’s all the other stuff?

This kind of almanac merges the Gregorian and lunar calendars, Chinese astrology, agricultural timings, and folk beliefs into a book of seasonal cycles, daily recommendations, and astrological predictions. There’s no one true form—hundreds of variations exist.

People use this information for many reasons: to mark the date, but also to determine the most auspicious times for certain activities, from crop planting to grand openings to funerals. Or, even more esoterically, to determine what direction to face when engaging in important tasks, like contract signing or worship. Much of this is still Greek to me, but more on that later.

The Yun Hai x O.OO Lunisolar Almanac

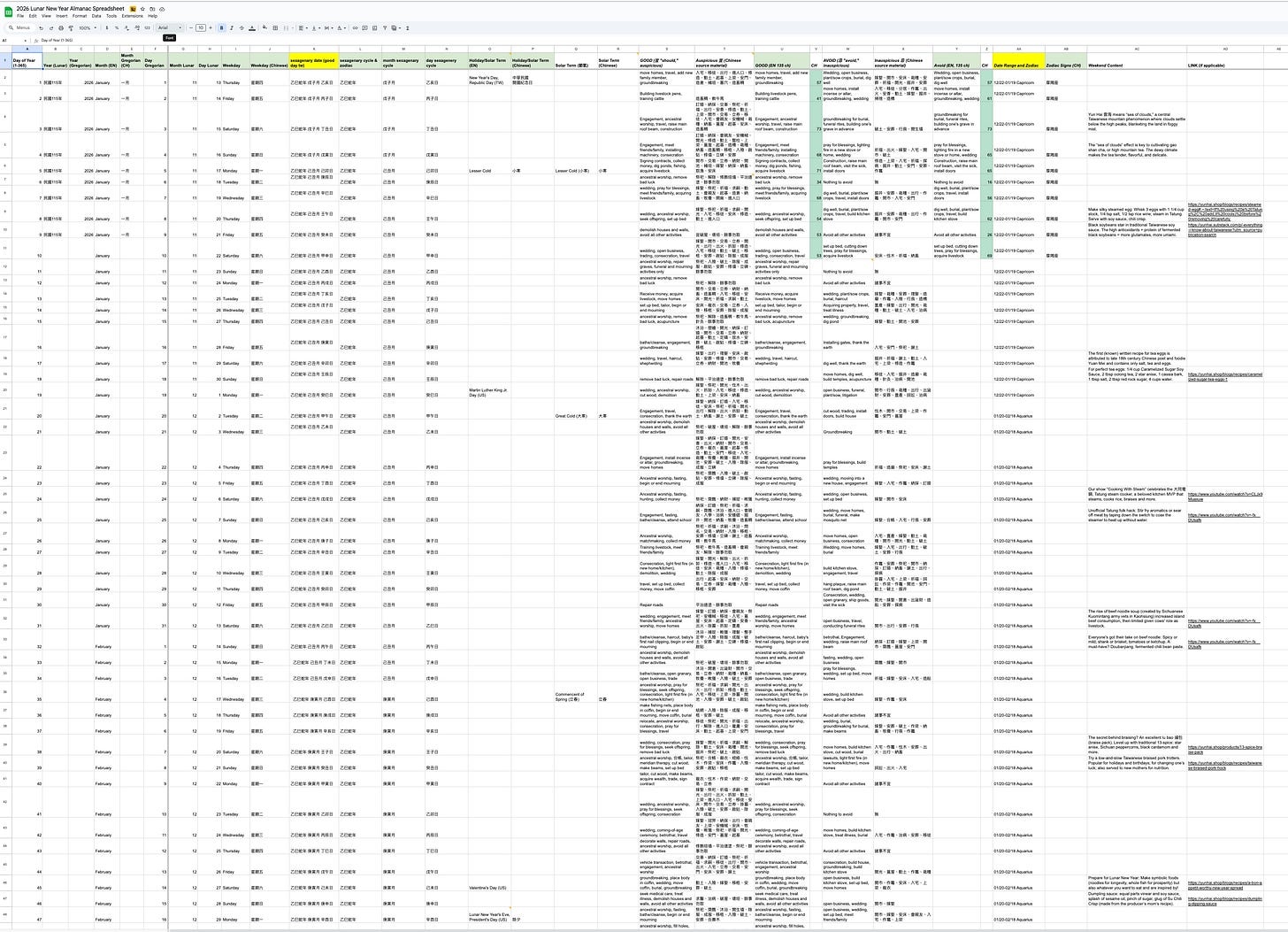

Yun Hai is in the process of designing our own 2026 lunisolar almanac, to be released for preorder this fall, in collaboration with Taiwanese design studio O.OO. Writing this in the middle of summer, 2026 feels like a long way off, but we’re in the thick of the design phase. Our project references traditional forms and verified Taiwanese sources of open source almanac data.

Sign up to be notified when it goes live.

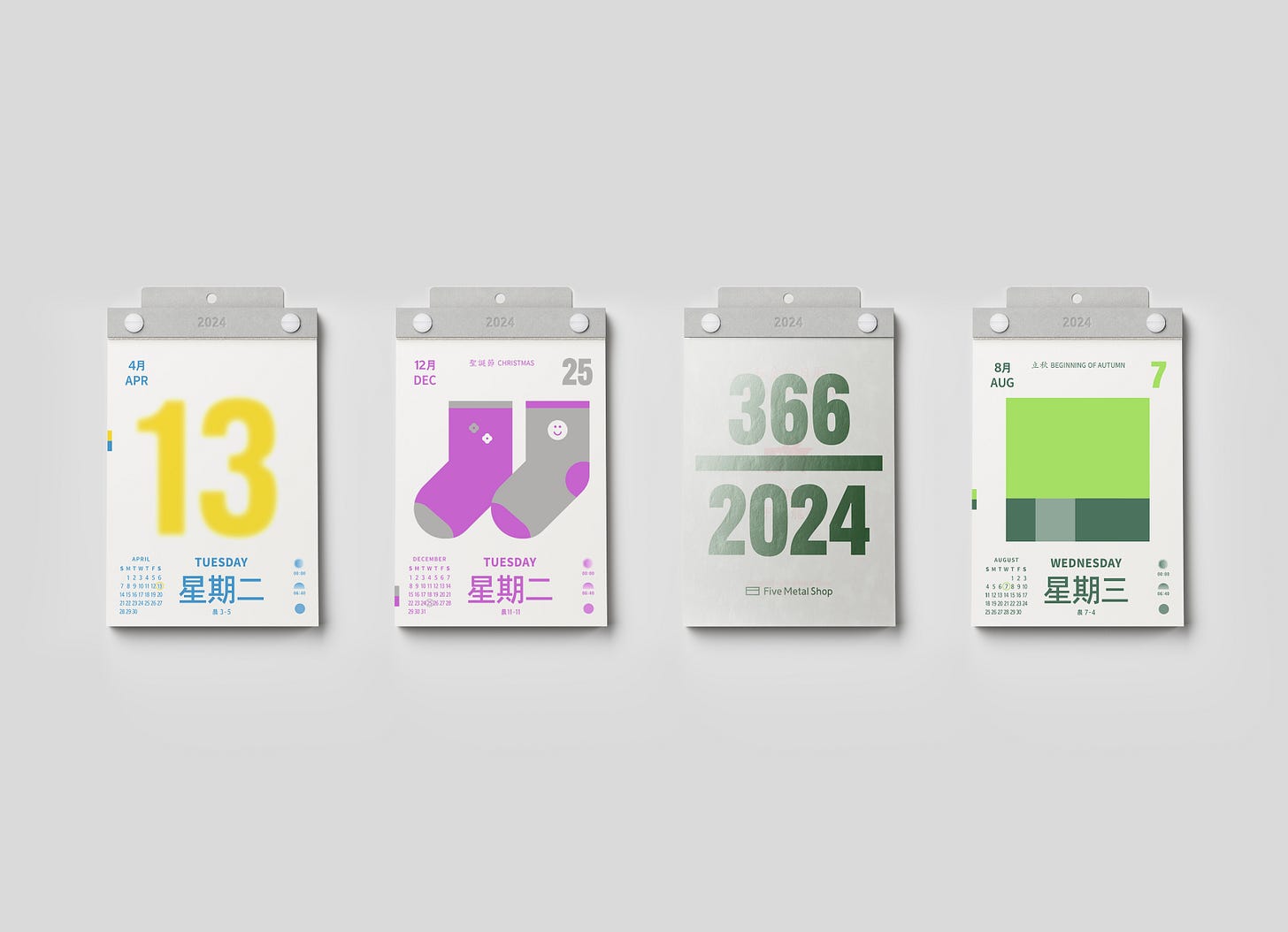

The project started as a follow-up to the now discontinued Five Metal Shop calendar, a Taiwanese almanac we distributed for a couple years (and to immense popularity) before it was halted for 2025. We’ve missed it so much that we were compelled to create our own, approaching it from a traditional and vernacular angle.

After working on the almanac this summer, I understand why Five Metal Shop eventually halted the project: it’s quite a thing to do every year. It involves managing 365 days worth of temporal and astrological data; cramming it all into a book small enough to be practical: engineering and prototyping a reliable tear-off mechanism (a factor of both backer card and paper type); and printing it all for a price affordable enough to potentially be ubiquitous. Sweat.

Happily, I got to spend a lot of time with the almanac concept, alongside designer Pip Lu and writer and activist Kimberly Chou 周存安, who wrangled most of the data. As we laid it out and examined traditional forms, I became fascinated by the origin of the information I once found to be impossibly cryptic, and it took on powerful meaning.

Our Cosmic Address

Almost all the information presented on these traditional lunisolar almanacs, from the simple date to the daily feng shui recommendations, are derived from our position in the universe. I came to think of the almanac as a sort of map, a highly technical system of calculations pushed through the black box of human culture to mark the passage of time based on our place in space.

Though I don’t subscribe to any particular astrological belief system, I do believe in seasons—cosmic, earthly, and personal. I believe in past lives, within our current selves and in the fluff we come from. I believe in the bittersweetness of the passing of time and the potential of the coming days. I don’t believe things are random, but I do believe they are mysterious. Energy doesn’t die, we’re in perpetual motion. The almanac reflects this.

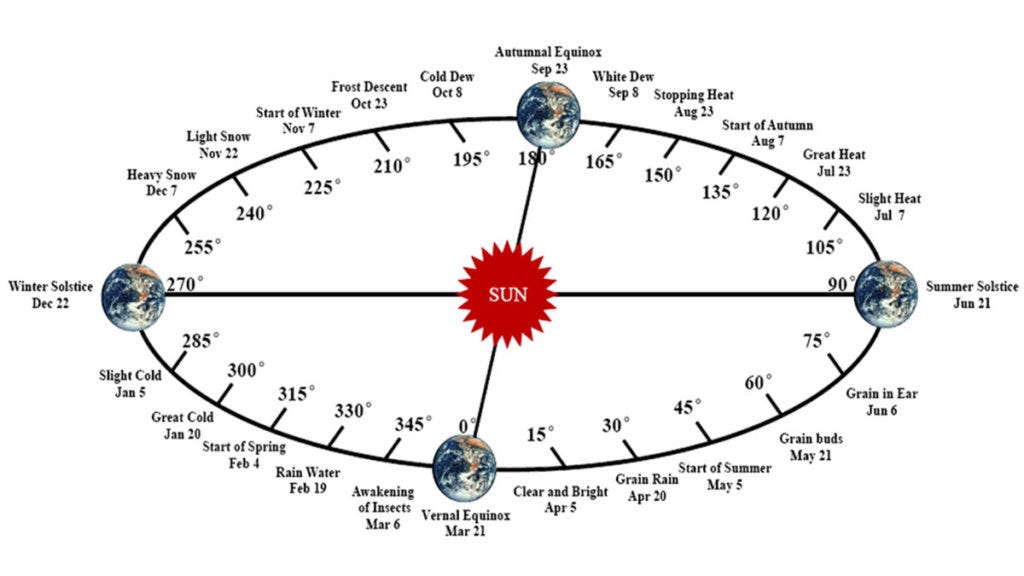

The Chinese zodiac animals are based on the position of Jupiter. The Lunar holidays and calendar are based on the position of Earth’s own satellite. Our contemporary Gregorian calendar is based on our orbit around the sun, dividing that time equally according to the speed of our revolution. But, solar terms, a way of describing our seasonal progression through the year, are based on dividing the sun’s observed trip around the earth by 15 degrees. Because the earth’s orbit is elliptical, these terms vary in length and don’t fall on the same Gregorian date every year.

In other words, each day has a cosmic address, marking our relative position to the observable or calculable positions of our neighbors.

I’m a Romantic to a fault. I write that with the capital R to refer to the late-18th century cultural movement, where the wild, sublime, unknowable, and imperfect captured the human imagination over the precise, controllable, intellectualized traditions of the Enlightenment. I seek the sublime, the too-big-to-be-knowable, and I really like the things in our daily lives that capture it in their banality. The almanac tracks our cosmic position, expressed plainly on a sheet of thin paper, through human interpretive and cultural systems. It both concretizes our present reality but also abstracts it into a set of rules, like a board game. And yet, it’s full of mystery.

In this week’s paid newsletter, I thought I’d share some of what I learned about the information included on a typical lunisolar almanac, a sneak preview of what’s to come.

Lunisolar Almanac Glossary

Here’s some background information about a few of the items we’re including in our calendar. A textbook could be written about each one, but this will get you started.

Sexagenary Date 干支

This Chinese astrological system for naming months, days, and years after zodiac animals and the five elements has been in use for over 2,000 years. It's based on a series of sixty combinations, made from the 10 Heavenly Stems (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water, repeated twice for their Yin and Yang sides, with different characters per occurrence) and the 12 Earthly Branches (Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, Pig).

For example: January 1st, 2026 is 乙巳蛇年 戊子月 乙亥日, or Wood Snake Year, Earth Rat Month, Wood Pig Day. On this day, one might avoid weddings but would potentially find good fortune in scheduling a move.

Have you ever noticed that sometimes Lunar New Year headlines will say something like “Happy Year of the Wood Snake?”

The English translation of the stem names is misleading, since there are two characters within each element that represent different ideas. For example, this year we’re in the year of the Yin Yi-Wood Snake (乙巳), which suggests adaptability, and not strength, like the preceding Yang Jia-Wood cycle.

Jia (甲): Yang Wood, representing strength and growth.

Yi (乙): Yin Wood, representing flexibility and adaptability.

Bing (丙): Yang Fire, associated with the sun and passion.

Ding (丁): Yin Fire, associated with candlelight and refinement.

Wu (戊): Yang Earth, representing stability and groundedness.

Ji (己): Yin Earth, representing practicality and nurturing.

Geng (庚): Yang Metal, representing strength and determination.

Xin (辛): Yin Metal, representing refinement and precision.

Ren (壬): Yang Water, representing wisdom and flow.

Gui (癸): Yin Water, representing depth and introspection.

Used together, the heavenly stems and earthly branches create sixty combinations, and the naming cycle resets once every combination has been used. Alongside solar terms (see next page) and other astrological factors, this system is foundational for determining auspicious vs. inauspicious days.

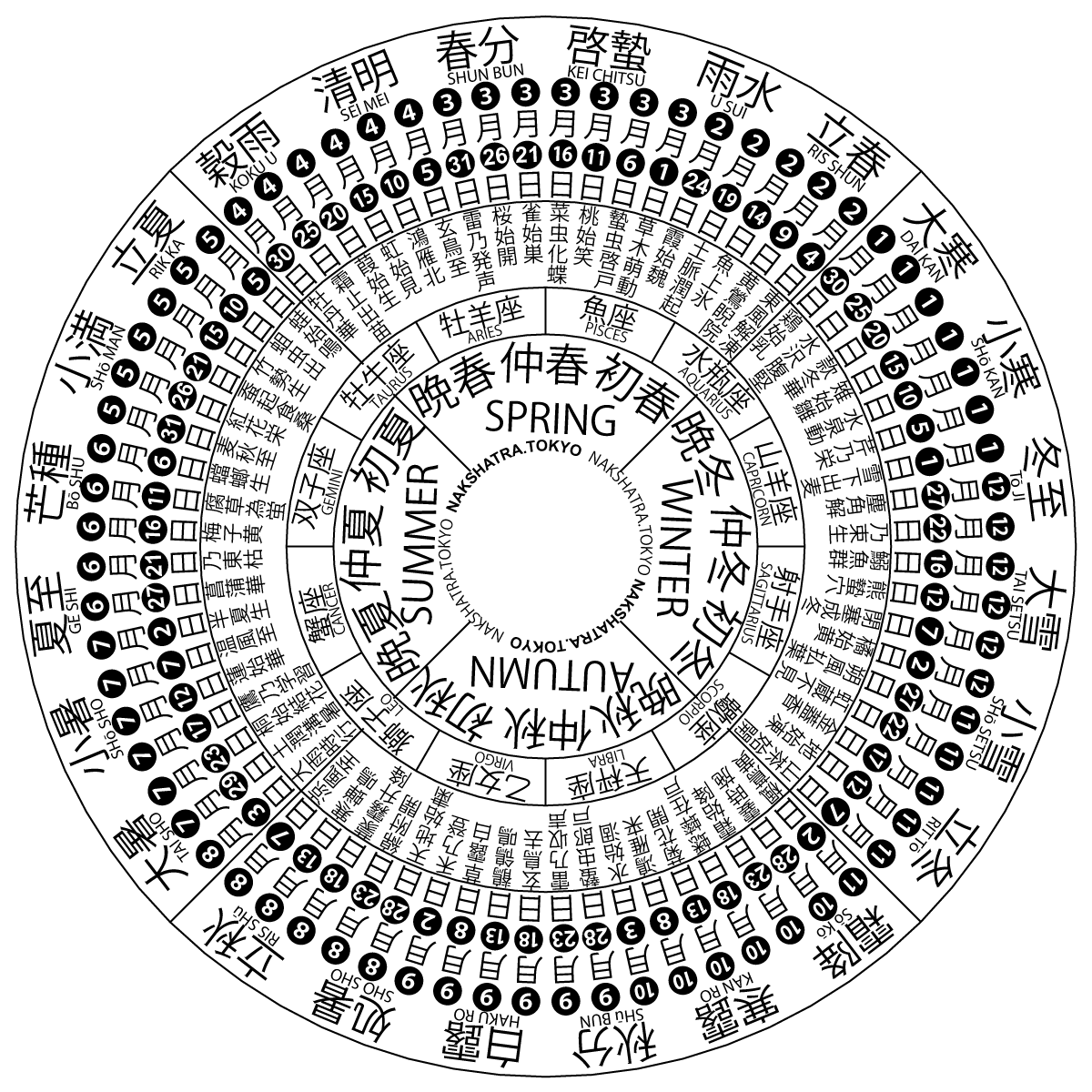

Solar Terms 節氣

Solar terms (or 節氣 jié qì) are 24 divisions of the solar year used in traditional Chinese calendars to mark seasonal changes and agricultural timing. They divide the year into roughly 15-day periods. These periods aren't calculated by dividing the 365-day year into 24, but by splitting the sun's elliptical path into 24 segments. As such, solar terms are related more to the placement of the solstices than the Gregorian year. Think of them as a precise division of the seasons, a more specific indication of spring, summer, autumn, and winter.

References to these periods are found throughout Taiwanese culture. For example, Lim Giong, a Taiwanese electronic artist, has an album entitled Insects Awaken or 驚蟄, the 3rd solar term. Definitely worth a listen by the way:

I love this description of the discovery of solar terms provided by Wikipedia:

According to the Book of Documents, the first determined term was Dongzhi (Winter Solstice) by Dan, the Duke of Zhou, while he was trying to locate the geological center of the Western Zhou dynasty, by measuring the length of the sun's shadow on an ancient type of sundial called tǔguī (土圭). Then four terms of seasons were set, which were soon evolved as eight terms; not until the Taichu Calendar of 104 BC were all twenty-four solar terms officially included in the Chinese calendar.

“Whatcha up to, Dan?”

“Oh just trying to determine the geologic center of the Western Zhou dynasty but discovered the four seasons instead.”

Here’s a full list of the terms and their meanings. The start date of each term varies annually, but the graphic below will give you a good idea of when each one begins (and where we are in relation to the sun at the time).

Spring (春)

立春 (Lìchūn) - Start of Spring spring begins

雨水 (Yǔshuǐ) - Rain Water increase of rainfall

驚蟄 (Jīngzhé) - Awakening of Insects hibernating insects wake up

春分 (Chūnfēn) - Spring Equinox equal length of day and night

清明 (Qīngmíng) - Clear and Bright the weather becomes noticeably warmer

穀雨 (Gǔyǔ) - Grain Rain rain beneficial for plant growth

Summer (夏)

立夏 (Lìxià) - Start of Summer summer begins

小滿 (Xiǎomǎn) - Grain Buds grains bud out

芒種 (Mángzhòng) - Grain in Ear grains mature

夏至 (Xiàzhì) - Summer Solstice longest day of the year

小暑 (Xiǎoshǔ) - Slight Heat start of hot weather

大暑 (Dàshǔ) - Great Heat hottest period

Autumn (秋)

立秋 (Lìqiū) - Start of Autumn autumn begins

處暑 (Chǔshǔ) - Stopping the Heat hot weather ends

白露 (Báilù) - White Dew dew becomes white

秋分 (Qiūfēn) - Autumn Equinox equal length day and night

寒露 (Hánlù) - Cold Dew colder dew

霜降 (Shuāngjiàng) - Frost's Descent dew becomes frost

Winter (冬)

立冬 (Lìdōng) - Start of Winter beginning of winter

小雪 (Xiǎoxuě) - Light Snow first snow

大雪 (Dàxuě) - Heavy Snow heavy snow

冬至 (Dōngzhì) - Winter Solstice shortest day of the year

小寒 (Xiǎohán) - Slight Cold start of cold weather

大寒 (Dàhán) - Great Cold the coldest weather

GOOD/AVOID

This designation refers to activities that are recommended or advised against on any given day, according to the cosmic conditions. "Good" refers to activities that would be auspicious. "Avoid" suggests things you might consider waiting on. Someone pointed out you could use this to determine when a wedding venue in Taiwan might be offering discounted rates; just look for all the dates where getting married is “to be avoided.”

The Chinese terms are:

宜 (yí) - "Good" or "Suitable"

忌 (jì) - "Avoid" or "Taboo"

September 18th, 2022, pictured above, was considered good for traveling or cleansing, but not ideal for major construction work. On that day, I happened to be taking family portraits, so I think I’m ok on all fronts:

Thanks for reading, and I hope this helps illuminate the lunisolar almanac. It’s worth taking a closer look next time you see one.

Just trying to locate the center of the Western Zhou Dynasty,

Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉

The ideas and opinions expressed in Studio Notes are mine, and don’t represent the larger Yun Hai organization. I read all email replies and comments, so please reach out. Photographs, unless credited, are by me. If you enjoyed this newsletter, share it with friends and subscribe if you haven’t already. I email once a month, sometimes more, sometimes less. For more Taiwanese food, head to yunhai.shop, follow us on instagram and twitter, or view the newsletter archives.